By PDA Insiders (Sally Cat and Brook Madera)

SallyCat's article here: http://www.sallycatpda.co.uk/2025/06/is-pda-autism-rethinking-diagnostic.html

Introduction

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) remains one of the most contentious and confusing neurodivergent profiles. At the heart of this debate is one persistent question: should PDA be recognised as a subtype of autism—or does it demand a category of its own?

To understand this, we need to trace the evolution of diagnostic systems and how PDA people became diagnostic refugees.

From PDD to the Autism Spectrum: The Collapse of Diagnostic Diversity

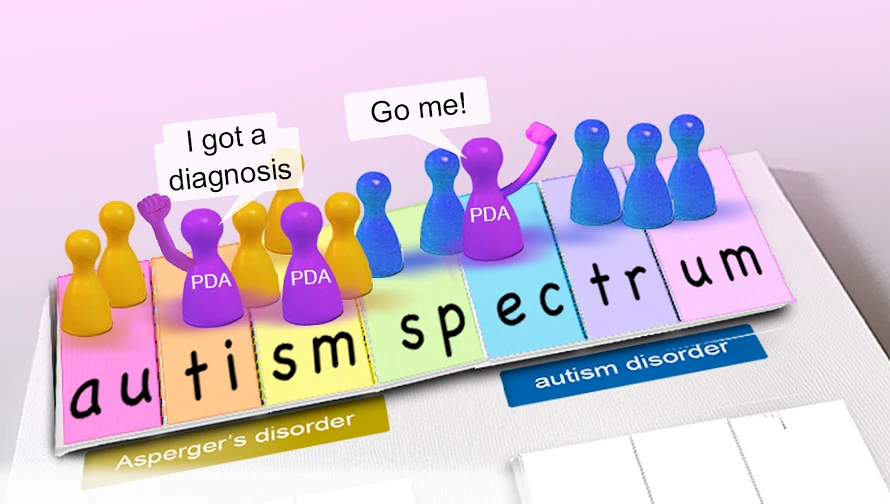

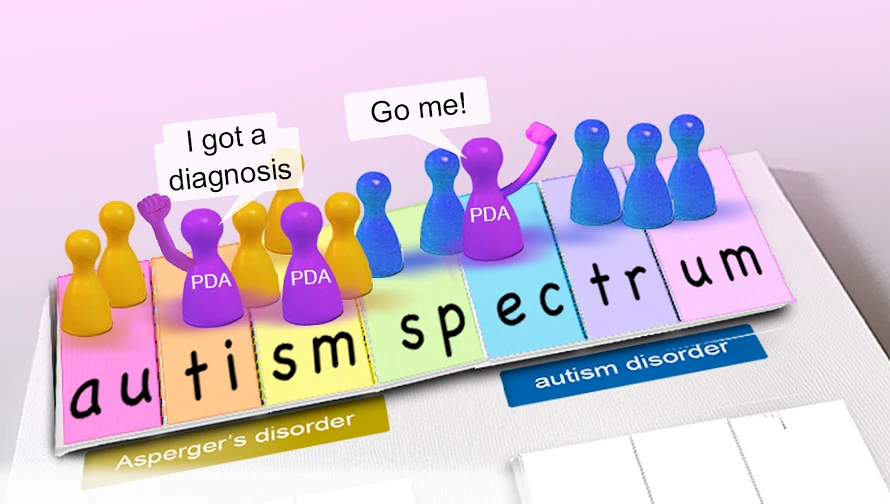

Under the DSM-IV, conditions such as autistic disorder, Asperger's syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) existed as separate but related diagnoses.

PDA was first noted, and named by, Professor Elizabeth Newsom who identified the profile in children referred to her during the 1980s who puzzled clinicians by seeming autistic in someways, but with marked differences. This classed PDA as slotting under the PDD-NOS category—an intentionally broad classification for individuals showing some features of autism but not meeting full criteria.(you can read more here)

However, when it was published in 2012, the DSM-5 collapsed these subcategories into a single diagnosis: autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The intention was to simplify and standardise diagnosis. But in doing so, all differences between neurodevelopmental conditions were flattened.

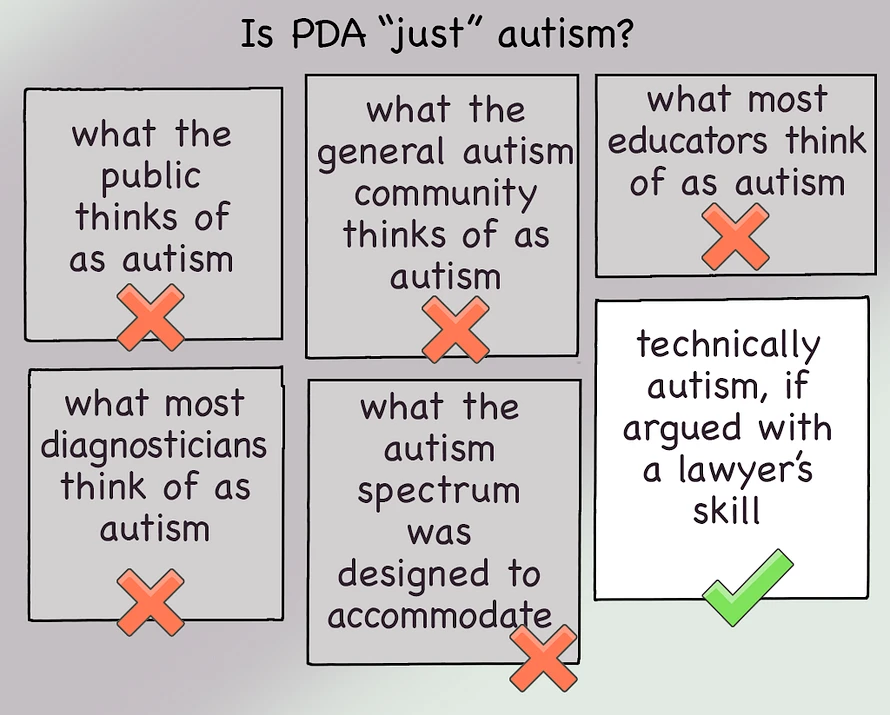

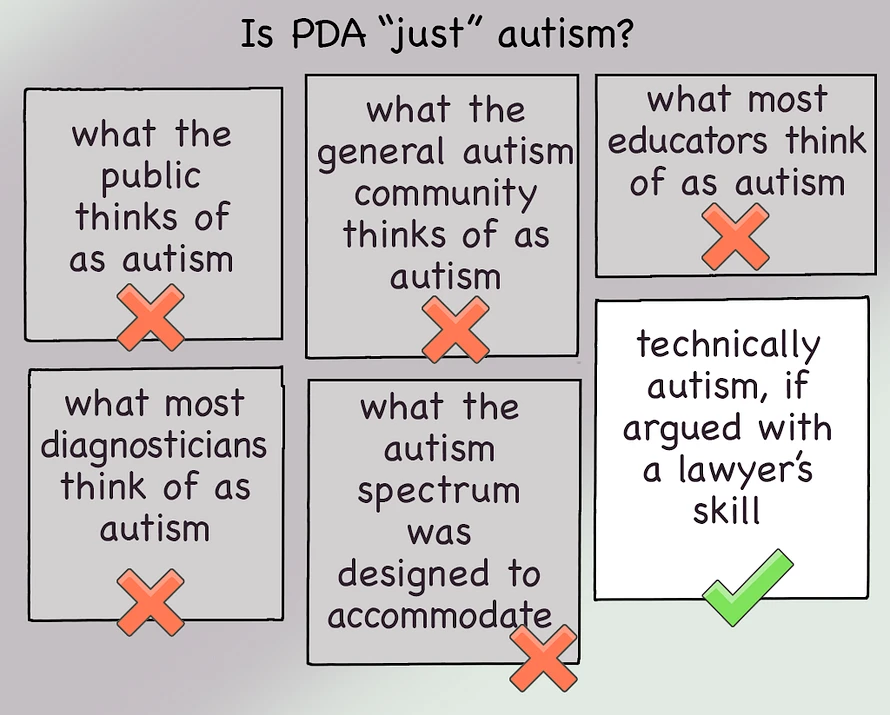

PDD-NOS vanished. So did the diagnostic space where PDA had unofficially resided.Since this time, the evolving use of terminology has continued to generate confusion. Although ASD is an umbrella term which PDA can be argued to fit, there has been a growing tendency to use ‘autism’ as the overarching term. In this sense, the correct term for PDA is ASD, not autism.

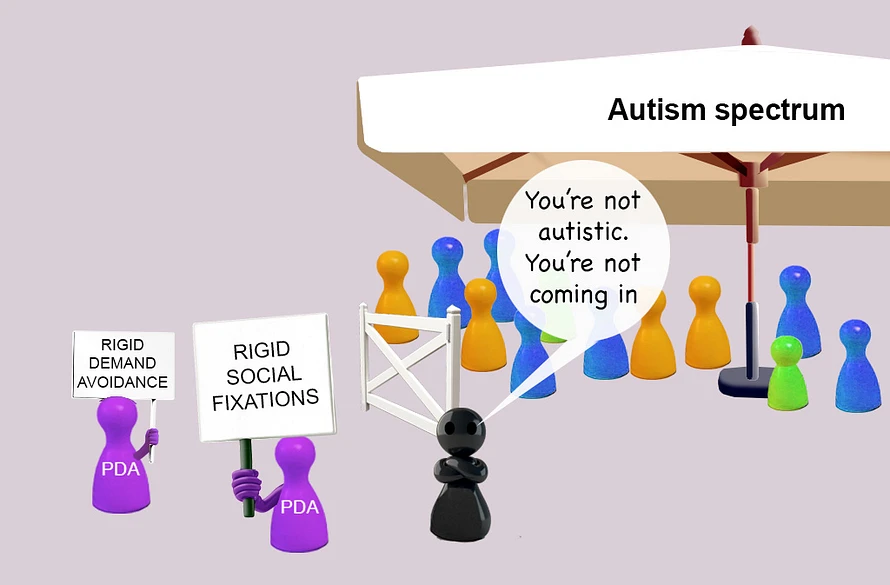

PDA Under DSM-5: A Square Peg in a Round Hole

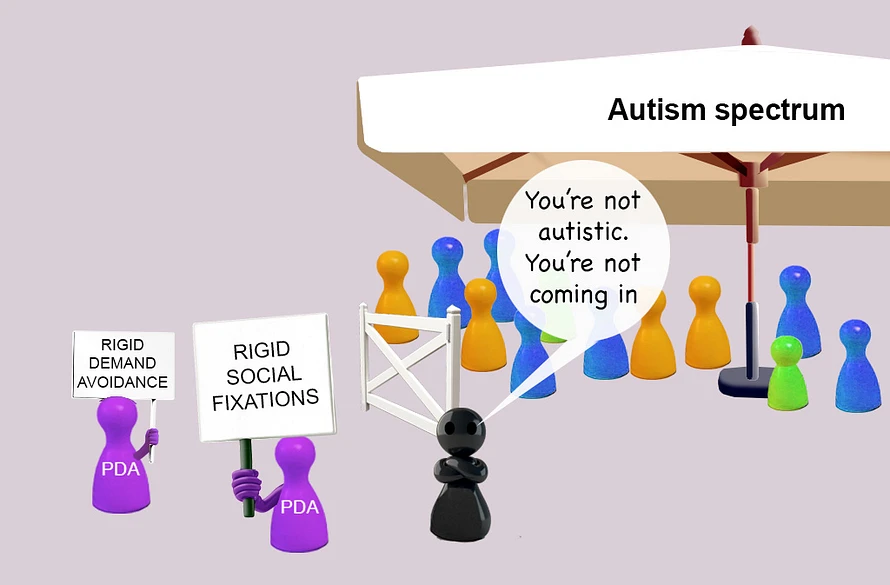

Post-DSM-5, the only remaining diagnostic route for PDA is autism spectrum disorder. But the fit is tenuous. PDA’s hallmark features—obsessive demand avoidance, surface-level social fluency, and intense emotional volatility—do not map neatly onto ASD criteria.To make a PDA diagnosis under DSM-5, clinicians must argue that PDA traits (like extreme demand avoidance and a fixation on social control) count as manifestations of rigid thinking—a core ASD feature. But for many PDA people, this feels like misrepresentation. They may not experience the kind of "rigidity" seen in classic autism; their behaviour is often highly adaptive and socially strategic—just not in neurotypical ways.

The result? Many PDA people struggle to obtain an autism diagnosis at all.

Writing for the British Psychological Society in 2015, Rebecca McElroy noted:

"Autistic children display rigidity through rules, routine and predictability; in PDA their rigidity is in their need to avoid demands and control situations, which can often lead to the child appearing extremely impulsive in their emotions and behaviour".

Erica Evans, who has coordinated support groups for PDA North America, believes perseveration (the tendency to repeat an action, thought, or behavior, even when no longer appropriate) is a form of rigidity that’s universal to PDA: "I have yet to meet a PDA person who doesn’t experience perseveration, but when the fixation might be socially driven it easily flies under most assessors’ radars."

Diagnostic Access vs. Support Reality

Here lies the paradox: an autism diagnosis opens access to crucial services and legal protections. But the supports those services provide are usually designed for classical autism, especially for individuals with social withdrawal, repetition, and sensory overwhelm.

For PDA people, traditional autism strategies—like visual schedules, structured routines, or reward-based compliance systems—can backfire, often escalating distress and avoidance. The approach is not just ineffective; it can be harmful.

It is important to note that PDA people may clash even with approaches designed to affirm autistic identities. This distinction is crucial, as such differences are sometimes overlooked with statements like, "Well, autistic people don’t like that either." However, there are well-recognized preferences and strategies associated with classic autism that can be profoundly triggering for PDA people, highlighting the need for more nuanced understanding and support.

In summary, this diagnostic catch-22 leaves many PDA people under-supported, misunderstood, and vulnerable in schools, workplaces, and healthcare systems.

Brook reflects:

"I’m pretty sure I masked autistically to be diagnosed properly. I think there’s nuance to why and how that was for me, like I’m constantly trying to feel understood by mirroring people and things."

Sally notes:

"When I gained my adult autism diagnosis, I thought I’d finally found my kin group and had a passport to the support I’d always needed.

But I wasn’t on the same wavelength as people in autistic forums I joined. As an example, they viewed the social communication skills I longed to learn as an evil thing non-autistic people tried to force them to do.

As for my support needs being met, this proved a mixed bag. My autism diagnosis was pivotal in winning my disability benefit entitlement tribunal. But practical support offered didn’t fit my needs, and was sometimes detrimental. For example, airport staff increased my anxiety by corralling me into boarding a plane last, then forced me to stay onboard until everyone else left, triggering my aversion to confinement."

PDA and the Identity Politics of Autism

Beyond clinical debates, the classification of PDA has ignited ideological tensions—especially within the autistic community.

The DSM-5’s unified spectrum was intended to reflect a core truth: that autism is not a series of distinct boxes but a continuum of traits. To argue that PDA is a “distinct type of autism” seems, to some autistic academics, a betrayal of this principle.

Scholars like Damian Milton have publicly critiqued PDA as simply being misunderstood autistic agency, a position that's made it vulnerable to professionals assuming PDA is a pseudo-condition--one invented or exaggerated by clinicians seeking diagnostic niches or by parents resistant to seeing their child as "truly autistic." Others, such as outspoken UK student, R Woods, have dismissed PDA as a myth, contending that its unique presentation is simply a variation within autism, not a separate entity.

From their standpoint, the notion that PDA is "different" undermines the unity and solidarity of autistic identity, whilst simultaneously leaving PDA open to assumptions of being rooted in racism because autistic BIPOC people are far more like to receive diagnoses of oppositional defiance disorder (ODD) than the less common diagnosis of PDA.

After discussing this with communications researcher and autism advocate Kaligirwa, PDA advocate Kristy Forbes told us she had realized:

"With the DSM-5, PDD-NOS as the umbrella for various ‘subtypes’ (for lack of a better word) was eliminated and so PDA, previously considered a PDD-NOS was no longer as such.

I haven't found anything that evidences that PDA is an autistic profile. I'm thinking it was just continued and presumed to be one, even though the PDD-NOS no longer exists.

I think it's important to unpack, particularly as Newson said, ‘PDA is a pervasive developmental disorder but not an autistic spectrum disorder: to describe it as such would be like describing every person in a family by the name of one of its members.

I dunno, for me, I am who I am. Autistic, PDA, ADHD, all the things. Still me."

With regard to differences between PDA and "general" autism, Libby Hill, a multi-award winning speech and language therapist specialising in PDA, says:

"PDA children often have no readily identified language difficulties. Indeed, they use language creatively to avoid demands, while autistic children often struggle to navigate language itself."

Institutional Harm: The Case of the National Autistic Society

The consequences of this disagreement are not abstract. In the UK, when the National Autistic Society (NAS) revised its webpage on PDA—stating that PDA was not a separate condition but just one way autistic people may express avoidance—the effects were immediate.

Schools and local authorities used this shift as justification to withdraw support plans for PDA children. Without a distinct identity, PDA people are invisible within autism services, but unqualified for alternative support pathways.

This policy decision, informed by conceptual debates, had real-world consequences for some of the most vulnerable children and families.

Brook comments:

"When you add to it that diagnosticians struggle to see beyond personal bias, or sexism, or [fill in the blank] and they hold power in deciding what someone is, or is not, it makes it even more triggering.

We don’t get to speak to who and what we are without that external validation."

Sally adds:

"Worse, some PDA people may lack the requisite rigidity of thought/behaviour to qualify them for autism diagnosis. This means that, under the current diagnostic system, a percentage of the PDA population is totally excluded."

Polar Views of Autism in the PDA Community

As we’ve seen, PDA’s relationship to autism is complex. Even the word ‘autism’ has shades of meaning, with a majority of people––including the autism community itself––viewing it as common ground between the former diagnostic categories of autism disorder and Asperger’s disorder. In fact, it was for this reason that the DSM-5 replaced individual pervasive developmental disorder diagnoses with the unified autism spectrum. But doing so made PDA a diagnostic refugee.

The truth is that many PDA people embrace being autistic. Eloquent arguments are made for PDA traits––such as perseveration––qualifying as rigid thinking, or behavior that meets the diagnostic threshold.

However, others identify as being PDA without diagnosable autism.

Each side of the PDA camp may view the other as deluded. For example, advocates for PDA being "autism" may be accused of shallow understanding.

Conversely, Brook notes:

"I know that one mistake made in the PDA advocacy corner is assuming that those who are PDA who don’t view themselves as autistic are suffering from ‘autistic-phobia’."

The truth may be that rigidity varies across the PDA population. This could explain the split between those who do, and don’t, identify as autistic. It might also explain the impermeable barrier some PDA folk run into when trying to gain autism spectrum diagnoses.

Sally recalls:

When I first suggested that PDA might be a standalone condition––this was back in 2016––some members of the PDA community were so angry that I tailspun into muteness, panic and overwhelm.

I didn’t drop the idea because other PDA adults were convincingly sure they weren’t autistic, and their exile from diagnostic recognition had triggered my social justice drive.

But, back then, having people shout that I was wrong made me freeze, and scrambled my thoughts.

We were all learning about PDA as best we could, but there was precious little information, and nothing at all about adult PDA.

Lots of people were strongly attached to the idea that PDA was autism. I continued to hold space for PDA existing without autism, but didn’t broadcast it from the metaphorical rooftops.

It’s taken this long for me to make sense of the conundrum in my own head; to distinguish the autism spectrum from autism; and the purpose behind the autism spectrum from technical arguments about whether PDA fits it.

The Ethics of Calling PDA "Autism"

Despite eloquent arguments, is it actually ethical to insist that PDA is autism? After all, the autism community fought long and hard to gain the autism spectrum as a unified home.

Arguing that all rigidity qualifies as autism disrespects the autism spectrum’s purpose of rehousing people who fitted the DSM-IV classifications of autism disorder and Asperger’s disorder. In this light, the term "autism" might most appropriately be used for people matching the common consensus of what autism is.

Following the same logic, arguing that PDA "is autism" equates to invading the autism community’s hard won homeland.

Would a Needs Based Approach be Better?

While we acknowledge that it's not our place to criticise fellow PDA folk’s self-identities, we argue that the priority should be meeting support needs.

The fact is that, no matter how passionately PDA is argued to fit the autism spectrum, doing so causes inappropriate, and even harmful support measures to be put in place.

Brook provides an analogy:

"If you have two kinds of badgers that need very different environments to live in, what’s most important? The fact that they are both badgers, or what they need to survive?"

In other words, although PDA can be argued to fit the autism spectrum, doing so causes inappropriate support to be offered.

Might it be better to rename the autism spectrum for a neutral word that describes PDA and "general" autism’s commonality.

Using Brook’s badger example, autism-badgers and PDA-badgers would slot into the family of neurodevelopmental badger disorders.

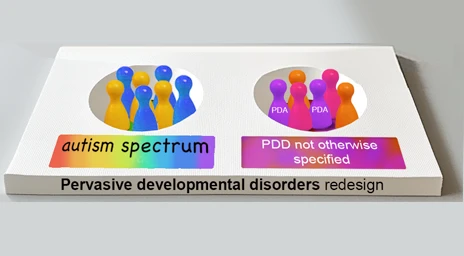

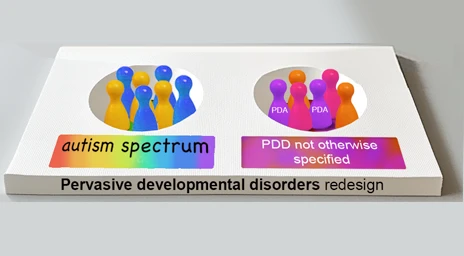

A Case for Bringing Back PDD-NOS

One solution to PDA’s diagnostic crisis could be bringing back the category of PDD-NOS (pervasive development disorder not otherwise specified) to sit alongside the autism spectrum.

Reclassifying PDA in this way would silence arguments that autism can’t be split into distinct profiles, and allow people to consider what PDA is in its own light.

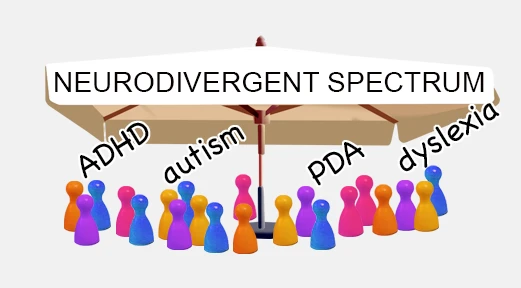

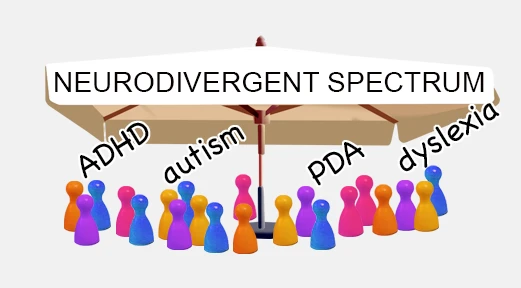

Is It Time for a New Neurodevelopmental Spectrum?

What’s becoming increasingly clear is that the autism spectrum may be too narrow a container for all neurodevelopmental realities. Perhaps the solution lies not in trying to wedge PDA into ASD, but in reframing the entire landscape.

Imagine a neurodevelopmental spectrum, a broader diagnostic and conceptual umbrella under which autism, PDA, ADHD, Tourette’s syndrome, and other neurodevelopmental conditions could sit as neighbours rather than subsets. This model would:

- Allow PDA to stand on its own without disqualifying it from support

- Acknowledge similarities between conditions without collapsing their differences

- Offer more accurate diagnostic labels that reflect real lived experience

- Avoid the gatekeeping and tribalism that currently define the autism discourse

On social media, James the Autistic Photographer states:

Autism is often a reflection of ADHD and vice versa. I truly believe these conditions are part of the same alternative neurotype which presents differently in different people.

Conclusion: Toward Inclusion Without Erasure

PDA may overlap with autism, but its differences are not trivial, delusional, or invented. Diagnostic structures that fail to accommodate these distinctions don’t just distort science—they harm people.

It’s time to move past the binary question of whether PDA "is" or "isn’t" autism. A better question might be: how can we build a diagnostic system that reflects the full richness of neurodiversity?

Until then, PDA remains a condition caught between categories—too autistic for some, not autistic enough for others—stranded in the no-man’s land of diagnostic ambiguity.

Want to Join the Conversation?

If you’re interested in reforming how we understand neurodiversity, share this article and help bring visibility to PDA people. Recognition matters. So does being seen for who you truly are.